ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

BOOK REVIEWS - ESSAYS (3)

The Coming Terror (1891) Is Barabbas a necessity? (1896)

The Coming Terror, and other essays and letters (1891)

The Daily Telegraph (15 April, 1889 - p.2) It is the intention of Mr. Robert Buchanan, in a forthcoming publication, to review the whole controversy on the subject of “Feminine Subjection and Male Chivalry,” recently discussed in these columns. He will at the same time animadvert on various phenomena of the day, with a view to the illustration of his parallel between the Rome of Juvenal and modern London. ___

The Liverpool Mercury (18 March, 1891 - p.7) Mr. Robert Buchanan is about to publish, through Mr. William Heinemann, a volume entitled “The Coming Terror,” and other essays and letters. Mr. Buchanan, if he is so-minded, should not be short of subjects for a volume with such a title. ___

The Derby Daily Telegraph (3 April, 1891 - p.2) Mr. Robert Buchanan will be on the war-trail next week. He calls his latest forged thunderbolt “The Coming Terror,” which Mr. Heinemann is to publish. I am told it is to be a scorcher. There is to be no mercy shown all round. No political section, no prominent individuality, will escape the essayist’s flail. Paternal Government and State Socialism are the convenient terms he uses to allow of a bitter attack on the powers that be, He will advocate equality of the sexes with absolute freedom of moral action, and he would like the literary man to write just what he thinks proper. Does this mean the suppression of the National Vigilance Association, or the summary abolition of our libel laws? Mr. Buchanan will survey mankind from China to Peru; in other words, he will tackle subjects as wide apart as Zæo, Mr. Stead, and Ibsen, and when the prophet opes his mouth let no dog bark. Let me hope his vitriolic indictment of things in general will do himself some good, if nobody else; but there is sure to be a run on the book. We are always glad to see ourselves as others (and especially Mr. Buchanan) see us. ___

The Speaker (4 April, 1891 - pp.402-403) SHORTLY before the appearance of “The Outcast: a Rhyme for the Time,” MR. WILLIAM HEINEMANN will publish a prose book by MR. BUCHANAN, “The Coming Terror, with Other Essays and Letters.” In this book MR. BUCHANAN reprints a number of his letters to the Daily Telegraph and other newspapers, together with several discussions on contemporary topics. The longest paper is entirely new, and consists of a dialogue between Alienatus, a Provincial, and Urbanus, a Cockney. In this portion of the book, as in others, it will be discovered that MR. BUCHANAN “hits hard all round.” His protest is against what he calls the “anti-social Socialism of the hour,” and against “special Governmental Providence in all departments.” He guards, however, against the charge of ultra-Individualism. “That duty which Society owes to the individual,” he insists, “the individual also owes to Society.” “A plague on both your houses,” is MR. BUCHANAN’S cry, alike to ultra-Socialist and ultra-Individualist. It is always, we fear, difficult to say on which side MR. BUCHANAN fights; although a savage adversary, he makes a dangerous ally. ___

St. James’s Gazette (13 April, 1891 - p.5) “THE COMING TERROR.” MR. ROBERT BUCHANAN’S NEW BOOK. Mr. Robert Buchanan is sometimes very right and sometimes very wrong; but, whatever we may think of the opinions which he happens for the moment to be upholding, we cannot but admire the vigour with which he slashes around him and the dexterity with which he sends straight to their mark his sharply tipped arrows. He is over-fond of phrases which do not look nice in print; and a perusal of his new book “The Coming Terror” (Heinemann) confirms the impression that he would gain in authority by a more careful restraint of expression. It is as easy to make the dessous too prominent as to commit the fault for which he castigates the Howells-like young man, and to pretend that there is no dessous in the most ladylike of worlds. With the exception of a few pages at the end, there is little in “The Coming Terror” which has not been read, over Mr. Buchanan’s signature, in the magazines and newspapers of the last year or two. Still his controversies with Mrs. Lynn Linton, Professor Huxley, the Ibsenites, and the apotheosized Young Person, were well worth reprinting. THE MODERN YOUNG MAN. “The Coming Terror” which Mr. Buchanan descries not very far ahead is, of course, State Socialism, with its enervating dead-levels, its emasculating dependence upon Grandmamma the State, its Providence made Easy for the lazy and the ignorant. The subject is large enough to afford abundant opportunities of excursions into other fields. One of the most entertaining, because one of the most aggressive, of these excursions is his essay upon the Young Man Critic. Says Mr. Buchanan:— With the passing of one brief generation, the world has changed; the youth who was a poet and a dreamer has departed, and the modern young man has arisen to take his place. A saturnine young man, a young man who has never dreamed a dream or been a child, a young man whose days have been shadowed by the upas-tree of modern pessimism, and who is born to the heritage of flash cynicism and cheap science, of literature which is less literature than criticism run to seed. Though varied in the genus, he is invariable in the type, which includes the whole range of modern character, from the young man of culture expressed in the elegant humanities of Mr. Henry James and Mr. Marion Crawford, down to the bank-holiday young man of no culture, of whom the handiest example is (as we shall see) a certain egregious Mr. George Moore. LIFE WITHOUT JOY. Passing from that which has been printed before, we come to the summary of his creed, which Mr. Buchanan appends to his book. He thus restates his case against the form of literature which has given us a drab and joyless view of life:— It appears to me that little or no harm can be done to the literature of Imagination by any hostile critic who is thoroughly in earnest. To find edification in the dreary family anecdotes and dingy back-parlour chronicles which are now called “dramas,” and to conceive life as drab-coloured and lugubrious throughout, is far less harmful than to have no taste for novelty and no zeal for humanity. The present apotheosis of what is mean and trivial and cheaply scientific—the present conception of Art as a series of dingy amateur photographs taken in the scullery during sunless weather—is only the inevitable reaction following the great period of loose and unfettered Ideality through which we have just passed. Presently, no doubt, it will be discovered that there is even more falsehood to Nature in a bad photograph than in a wildly executed painting; that no amount of truth to outlines and to shadows, no obtrusion of minor details, can compensate for the glow of light, of colour, of imagination. In the meantime, the craving for Photography in Literature may serve some good purpose if it leads men to be zealous for general truth of presentation. There will always be critics who are colour-blind. There will always, on the other hand, be writers who find in Nature not merely one common black and white, but all the radiant colours of the prism. ART AND MORALITY. There is no end to discussing the relations of morality to art; and we get Mr. Buchanan’s view of that troubled subject in the following paragraph:— The impeccable albino of Mr. Howells is just as much tainted with Egoismus as the nerve-shocking negroesque M. Zola. The self-analyzing and hypercultured young lady of Boston is as disagreeable in her superfinity as the nevrose heroine of “La Curée.” In either case Morality has poisoned and perverted Art. Here, as in other developments of the disease, I see in the so-called Gospel of the Ego, not a new revelation, but the last slimy trail of the Goethe system of ethics, shown in productions which, like the forgotten and worthless portion of Goethe’s work, were devoid of imagination and true human sentiment. What is new and immense to the young men of the ferociously “moral” newspapers has been familiar and detestable to me from the first moment I began to think and write. Where they find literary salvation I have found only the last dregs of a Devil’s gospel which has corrupted almost every branch of modern literature, and which, had Heaven not sent the world its literary knights-errant in Victor Hugo and Dumas, would have long ago destroyed all poetry in the world. To them the moral of the Ego is novel; to me it is as old as the “Elective Affinities” and Goethe’s self-culture, with little new in it, and that little untrue, and delivered without a gleam of consecrating insight. “ZOLA WITH A WOODEN LEG.” Mr. Buchanan never enjoys himself more than when he can toss and gore the sainted Ibsen. And he does it in such a way as to make the Ibsenites frantic; for it must always be remembered that the critic who makes fun of the new prophet hurts the Ibsenites rather than Ibsen. Mr. Buchanan here sums up his opinions upon the Gabblers:— One of my critics has abused me roundly for describing Ibsen as “a Zola with a wooden leg.” Another writer avers that “A Doll’s House” is the only play which has not “bored” him within the last few years, and adds (what is more to the point) that the nightly “storm of discussion” over Ibsen’s “ethics” is a proof of the dramatist’s genius and originality. Now, as a matter of fact, nothing is so easy as to outrage common sense, and so arouse discussion and opposition; nothing is so difficult as to please, to refine, and to charm. A playgoer witnessing the great masterpieces of dramatic literature does not become polemical; he carries away with him the pathos, the solemnity, and the calm of life itself. He has been to a theatre, not to a debating-room; he has been enjoying a work of Art, not a feverish and irritating platform controversy. It has ever been the aim of the great dramatists, from Sophocles downwards, to magnify the divine meaning of life, to depict that truth which is beautiful and spiritualizing. The mission of prosaists like Ibsen is the mission of dullards like Zola—to shock and to revolt us with the meannesses of life, and to assume that those meannesses most abound where Religion and Morality are most powerful. My callow critic is not merely disgusted with the modern dramatist; he describes the average home as a “harem,” the domestic affections of average men and women as stupid and conventional, the religious instincts of average humanity as instincts “he grew out of before he was born.” The same jaded and foolish creature who sees in Ibsen’s Nora a living woman representing Woman in the Abstract, would see in the banalities of “La Terre,” if produced upon the stage, a glorious lesson convincing us of the monkeydom of humanity. We want no such lesson, for we have had it of late years ad nauseam. ___

The Times (16 April, 1891 - p.10) THE COMING TERROR, and other Essays and Letters, by Robert Buchanan (Heinemann). The strength of Mr. Robert Buchanan’s opinion is well known—better known, indeed, than his opinions themselves. His own account is that he is a moderate individualist, who defends freedom with one hand and the reasonable conventions of society with the other—a very commendable attitude, in principle. How far this principle accounts for all his furious onslaughts upon things and persons it would take some time to discuss; but there is certainly something in Mr. Buchanan’s rather cross-grained mood which suggests the idea of a bull which lives in a phantasmagoria of red rags. All that can be affirmed is that some of the objects of this critic’s aversion—Socialist levellers, mouchard journalists, municipal meddlers, Ibsenite emancipators of society, and others—well deserve the caustic things he says of them; while in one and all of his sallies, whether extravagant or not, he displays an exuberance of pungent expression that is itself enough to secure the amused attention of the reader. ___

The Echo (16 April, 1891 - p.1) BOOKS AND AUTHORS. Like a hawk among the dovecots comes Mr. Robert Buchanan upon the critics and criticasters, the log-rollers, and mutual adulators, the literary ’Arrys, and the ’Arrys pure and simple of the period. Every healthy soul, whether it accepts Mr. Buchanan’s teachings or not, will heartily welcome his book of collected papers, “The Coming Terror and other Essays and Letters,” published by Mr. William Heinemann. In these times of cant, convention, and mawkish sentimentality, an article or book by this strong, fearless, vigorous writer, with his detestation of shams, his keen insight, and high ideals in literature, life, and art, is as a breeze from sea or mountain in the stuffy atmosphere of a hot house or a hospital. He stands up against the “wave of mock morality,” which, he says, is threatening to destroy much that is beautiful and pleasurable in life, in literature, and in art. He dreads the advent of State Socialism, which to him means “the greatest tyranny of the greatest number. Every institution, however peaceful, however beautiful, is to be destroyed and trampled down under the hob-nailed boots of Demos. Intellectual activity itself will soon be regarded as a dangerous form of competition. . . In proportion as we limit the freedom of the individual we retard the progress of the race, destroy human character, debase human intelligence, and arrest the development of the social conscience.” But, of course, the Socialists whom Mr. Buchanan attacks would reply that this “freedom of the individual” can never reach its fullest development except in a Socialistic State; and, to say the least, their arguments are forcible. Mr. Buchanan and Mr. Webb are in politics the opposites of each other; they should be read in conjunction. When Mr. Buchanan leathers his modern young man, one wishes more power to his elbow. The sort of young man whom he belabours is by far too common to be ignored. The modern young man as critic is Mr. Buchanan’s special aversion—he is the ’Arry of the doleful countenance, who never was a child, who mixes up Lecky’s “Rise and Fall” with Gibbons’s, who professes admiration for Walter Pater, but who “frankly informs us that he is immoral and indecent, and asserts that those who pretend to be otherwise are simply hypocritical.” By the way, it is a pity that so gifted and independent a critic of life, literature, politics, and art has not an “organ” of his own. Mr. Buchanan is by far too individualistic, too unconventional for the majority of editors. What about that monthly Review which Mr. Buchanan announced he was going to start? ___

The Speaker (18 April, 1891 - pp.457-458) MR. ROBERT BUCHANAN’S TEMPER. IN one of the papers which he has just collected and put forth under the title of “The Coming Terror” (Heinemann), Mr. Robert Buchanan suggests that an essay should be written On Certain Terms of Opprobrium. We have not the pen of “A. K. H. B.,” but the suggestion is tempting, and with Mr. Buchanan’s book before us we hasten to do our little best. “Sir, you have been, in your time, a writer of promise. For reasons which, no doubt, were sufficient in your eyes, you turned aside to produce work which differs in quality from that which was expected of you and from that which the ‘young men,’ who excite your bile, have chosen to admire. Why should you be angry? You have the sincere admiration of thousands who, in the Vaudeville Theatre or the Adelphi, look upon you as the foremost playwright, poet, ethical teacher of this generation. Experience has shown, a thousand times, that popularity of this kind is only attained at the price of a certain amount of contempt. You chose it, and we hardly see what right you have to grumble at paying. After all, you have the profits: the world rewards you in all but esteem far more liberally than it rewards Henrik Ibsen or Mr. Henry James. If Mr. Buchanan will attend to this mild remonstrance, we will make bold to ask him further, Why he should hate and disparage every man living whose work has attained any measure of success? He hates, as far as we can see, all his fellow playwrights: this book contains sneers at Ibsen, De Goncourt, Mr. Pinero, Mr. Grundy, the writers of the “Great Pink Pearl,” Mr. W. S. Gilbert, and Mr. Stevenson. He hates all the dramatic critics he has occasion to mention. He hates at least nine out of every ten novelists. M. Zola is a “negro”: Mr. W. D. Howells an “albino”: Mr. R. L. Stevenson a “hard-bound genius in posse”: of “Treasure Island” we hear that “at its best it is worthy (though that, indeed, is no little honour) of Mr. R. M. Ballantyne.” Mr. Buchanan has “no personal sympathy whatever with the diseased views of human passion taken by Count Tolstoi”—but an impersonal sympathy, perhaps: Ouida is “that classic of the Langham,” Mr. Rider Haggard the spoilt child of “nepotic criticism,” and so on. As for the reviews and newspapers, he quarrels with the Quarterly, the Edinburgh, Punch, The Times (“great Cockney organ,” “great organ of British Philistia,”), the New Journalism (“Babbage’s Organ in the Street,” “Tower of Babel,” “feeding the weak appetites of the community with the garbage of the latest news”), the Monthly Reviews (“reviews of inanity”), the Pall Mall Gazette (“journal of abominations”), and Mr. Andrew Lang (“a Cockney of Cockneys,”—wears kid gloves). Then there is Mr. John Morley—and Professor Huxley—and—we need not extend the list. In his large heart Mr. Buchanan can find room to hate them all. ___

The Speaker (18 April, 1891 - p.463) MR. GEORGE MOORE and MR. ROBERT BUCHANAN are very good enemies, and fate seems to have determined that even in accidents the one shall not get the better of the other. The first edition of MR. MOORE’S new book had to be recalled on account of a printer’s error; and so had the first edition of MR. BUCHANAN’S, although the error in the latter case might be mistaken for a joke of the publisher’s. “The Coming Terror. ROBERT BUCHANAN,” sans phrase, appeared on the cover. There is great virtue in “by”; and MR. HEINEMANN has inserted it. ___

The Leeds Mercury (21 April, 1891 - p.8) The first edition of Mr. Robert Buchanan’s new book, “The Coming Terror,” has been exhausted within a few days of its publication. ___

Glasgow Herald (23 April, 1891 - p.9) (1) The Coming Terror. The bulk of this characteristic volume with the sensational title has already appeared in an ephemeral form. Mr Buchanan ingenuously republishes, “at the request” of many correspondents, with a “selfish yet two-fold”—why “yet?”— aim. In the first place, he conceives that these obiter dicta may by and by be useful to readers of his “less desultory contributions to literature;” in the next, in republishing he has an opportunity of restoring one or two passages which were “too outspoken for the columns of the daily newspaper of the period.” “From the first moment I began to write,” Mr Buchanan takes occasion to confide to our sympathetic ears, “I have been endeavouring to vindicate the freedom of human Personality, the equality of the sexes, and the right of Revolt against arbitrary social laws conflicting with the happiness of human nature.” From which the reader will perceive that Mr Buchanan is even more resolutely determined than usual to take himself seriously. Indeed, “The Coming Terror” naturally falls into two moods—one in which the author unconsciously poses as a gravely picturesque, fervidly eloquent, enthusiastically visionary Socialist (“in the good and philosophical sense”); the other in which he refuses to treat otherwise than with half-amused, half-scornful ridicule certain well-known yet altogether no-account persons—Bank-holiday individuals, creatures in Cheap Literary Suits, and other nonentities who share in common the melancholy disadvantage of youth. In the first mood, in spite of his exuberant vocabulary—possibly, after all, in some measure on account of it—Mr Buchanan is apt to become tedious and even dull in the long-run. For a time, however, the poetic comedy of the situation is entertaining, and the declamation of the “higher Socialism,” lit up with flashes of racy personality, is piquant and novel enough. It is refreshing to find the Home Secretary described as a political Pilate Punchinello, Lord Wolseley as a droning military Person, Professor Huxley as our new Daniel come to judgment, “poor Carlyle” as St Thomas of Chelsea, Mr Labouchere as the Paul Pry of journalism and the Scapin of politics, a haunter of the back kitchens of the aristocracy, and a counter of the candle-ends of the governing classes; Mr Parnell as the Perseus of Ireland, and Mr Buchanan himself as the champion of latter-day Rousseauism, the reconstructor of society, the denouncer of the emerging Demogorgon, the propagandist of a Christianity which after all “these nineteen sad centuries” has, it appears, “never been tried yet save by a few isolated individuals, from Father Damien backwards.” To do Mr Buchanan mere justice, his aims and intentions are of the worthiest. The burthen of the remediable misery in the world oppresses him, and he would have it cast off forthwith. Wherein who will not sympathise with him? If only he would keep out the King Charles’s head of his uneasy personality, who would not be deeply interested in the memorial, however imperfect and occasionally mistaken it might be? But here, as elsewhere, Mr Buchanan’s colossal belligerent individuality obtrudes too persistently on the reader’s attention; the fluent periods of his facile but unpractical invective sweep on without that restraint and that resourcefulness of suggestion which one attributes to the philosophic mind; and if warmth of feeling, generosity of intention, an eager philanthropy are abundantly in evidence, these admirable qualities are marred by exaggeration, cock-sureness, self-complacency, and, indeed, a certain amusing arrogance. Could anything, for example, be more ludicrously impertinent or preposterously unpractical than the stilted and pretentious letter to Mr Matthews respecting the imprisonment of Mr Vizetelly, the publisher of a work by a certain M. Zola, to whom, though he be au fond a dullard, Mr Buchanan has “again and again taken off his hat in open day”—mark the frank audacity of the good, philosophical Socialist—because the said M. Zola, regarding pigsties as the only foreground for his lurid moral landscapes, appeared so much better and nobler than Mr Buchanan himself, “in so much as he loved truth more and feared consequences less.” Here are a few noteworthy passages in the letter:— “Right Hon. Sir,—You are, I understand, a Roman Catholic. I am a Catholic plus an eclectic. I have the highest respect for the creed in which you believe, since it is perhaps the most logically constructed of all creeds; but while I admire the logic I do not admit all the premises, and cannot consequently follow you to all its conclusions. Is it too much to hope, however, that even Roman Catholicism has shared the fate of other beliefs, and been shorn of many of its imperfections? . . . . . . I can assure you, Right Hon. Sir, that it is in no spirit of levity that I, who have little love for Roman Catholicism, suggest a way in which the Church Infallible may yet be saved. That way is, as I have suggested, to perform a latter-day miracle, and cast in her lot with the Church of Free Thought and Free Speech. . . . . . . The man who says that a Book has power to pollute his Soul ranks his Soul below a Book. I rank mine infinitely higher.” One would have liked to watch the Home Secretary’s face as he read—if he did read—this marvellous farrago. In this same communication, however, a delicate suppression of the author’s claims to distinction among “the great writers who have been canonised by Humanity” may be noted with approval. “To come down to contemporaries,” Mr Buchanan informs the Home Secretary, “I think Mr Browning might be adjudged an offender against the law of modest reticence, and Mr George Meredith a revolutionary in the region of sensuous passion.” Why have we no mention of such well- known novels as “A New Abelard” and “Foxglove Manor”? We need not here do more than make special reference to the controversy with Professor Huxley on the question, “Are men born free and equal?” It would be a piece of foolish temerity were we to deal with the Socialistic theories of Rousseau, seeing that Professor Huxley, “admirably as he is equipped for the light skirmishing of popular knowledge, fails altogether to understand the great French idealist.” The “uncrowned poet” makes no such failure, but it is curious that he has not observed that as a matter of historical fact if “all human beings stand, so far as moral rights are concerned, in the same practical category,” they do so not through any “law of nature”—whatever that may mean—but in virtue of that very civilisation which is alleged to have “destroyed to a perilous extent men’s natural freedom and equality.” Nor need we dwell on the dialogue regarding “The Coming Terror” except to note its chief and most sinister characteristics are:— “1. Political Tyranny of Majorities, culminating in Providence made Easy, or so-called Beneficent Legislation. Such are the horrors, or at least some of them, which will accompany, and are in some measure even now heralding the emergence of the Demogorgon. Respecting all which matters, as far as we can perceive, Mr Buchanan suggests no distinct and practical remedies beyond a reform of the criminal law withdrawing the prerogative of mercy from Pilate Punchinello. What possible schemes he might be prepared to propose it is not for us to surmise, though the following passionate declaration looks ominously like the lowest rather than the higher Socialism:— “I cannot calmly leave the regeneration of things evil to the slow and certain evolution of the corporate conscience; I feel that there is much to be said for the advocates of a more active social reorganisation, and I am not so convinced as Mr. Spencer of the necessary sacredness of contracts, or of the wisdom of holding them inviolable.” And yet one would imagine it to be to the evolution of the corporate conscience that one must look for all real regeneration; and if the sacredness of contracts is not to be held inviolable, what is? It is in the second mood of the volume, however, that the reader will find Mr Buchanan most entertaining. In “The Modern Young Man as Critic” and in “Imperial Cockneydom,” for example, there is provocation to inextinguishable laughter. Nor is one’s amusement diminished by the consciousness of how easy it would be for, say, the Young Man in a Cheap Literary Suit or the Bank- holiday Young Man to hit back hard. Of course there is much between the covers of “The Coming Terror”—witness the estimate of Ibsen, “Emma Wade’s Martyrdom,” the “Apotheosis of the Gallows”—with which it is a pleasure to agree with the author, and of course, too, there is ample evidence everywhere of trenchant literary faculty. On the whole, however, the book is a characteristic and diverting, rather than a convincing and helpful, contribution to the controversies of the day. (1) The Coming Terror, and other Essays and Letters. By Robert Buchanan. London: William Heinemann. ___

The Speaker (25 April, 1891 - pp.496-497) A LITERARY CAUSERIE. THE SPEAKER OFFICE. LET us consider the appearance of the common pen. I have been looking at my own, and confess that it appals me—a mean, malefic weapon, without strength or calibre to strike a man to the heart and kill him outright, but designed rather to scratch and prick and instil poison. I protest that it is the ugliest, basest instrument in the world, and admire the ancients who refused to discriminate in speech between it and the assassin’s dagger. Later ages feathered it and diverted attention from what Americans call the “business end” by calling it a pen; but even so it looked like a poisoned arrow. There is a picture of one on the cover of Mr. Buchanan’s new book, and across it runs this legend—“The Coming Terror.” It is not a natural weapon for a man who means to speak and show kindness to his fellows. To begin with, it is so abominably tactless. Set me down with my enemy; give me a pipe of tobacco; and it is odds that within half an hour we come to terms, or at least to respect each other. An inflection of the voice, a softening of the lines about the mouth, an honest humanity in the eyes, will smooth out hatred and cleanse the talk of spitefulness. But a man with a pen tries only to be smart; he strikes cruelly and unfairly because he cannot see how his blows fall; and this is the reason, I suppose, why two-thirds of all that is written from day to day is bad in breeding and savage in temper, and why men of letters speak of each other in language which the bargee would reserve for moments of extraordinary irritation. The bearing of a doctor towards his rival is decorous, urbane, brotherly almost. Two advocates hotly fighting a case will preserve, by easy consent, the dignity of their common profession. The kindly comradeship of actors is well known. Clergymen will take one another’s duties. But the “literary man” is a savage while engaged in his work. “The Republic of Letters” is meiosis for rank anarchy; and its members appear to have no regard at all but for themselves and certain dead men. Curiously enough, it is the older men who exhibit most truculence, and render respect for age so very difficult. Conversely, finding their old age unhonoured they become yet more truculent, assailing new ideas with every kind of misrepresentation. Consider, for example, the recent treatment of Ibsen’s plays. Certain young men found something in these plays to admire—not to worship. I suppose there is not a single young man of letters in this country who really prostrates his intellect before Ibsen. The “worship” was first suggested in such phrases as “the Ibsen craze,” “Ibsenity,” “Ibsenism,” all invented by Ibsen’s enemies; and only received the faintest colour of probability from the energetic rejoinders that all this detraction called forth. But what, in any case, can be more deplorable than the temper displayed in Punch, week by week, and the sneers at Ibsen which it publishes in and out of season? This paper has hitherto appealed to mankind by its humour, and its humour has been of the sanest, kindliest sort—the humour of Leech and Keene. But in these attacks on Ibsen there is neither humour, sanity, nor kindliness, nor anything, indeed, but bad blood: and those who have admired Punch from their youth up, and have laughed over M. du Maurier’s perfectly good-humoured ridicule of the defunct “æsthetic movement,” can only feel sorry that, under an editor who is also a playwright, Punch should contain mere abuse of another playwright. Surely we might easily have been spared these attacks, even if the editor’s delicacy of feeling had not forbidden them. When a paper so catholic in spirit as Punch comes to be written for the aged by the aged, it is time to draw attention to the petulance of our older men of letters. There is Mr. Robert Buchanan, for instance. “Frankly,” he cries, “I do not know what the Modern Young Man is coming to!” Then why, in the name of reason, does he go on to contend that the Modern Young Man is coming to perdition? “The faith which is life, and the life which is reverence and enthusiasm” have been denied, he asserts, to the youth of this generation. “The sun has gone out above him, and the earth is arid dust beneath him. He has scarcely heard of Bohemia, he is utterly incredulous of Arden, and he is aware with all his eyes, not of Mimi or of Rosalind, but of Sidonie Risler and Emma Bovary,” etc. etc. Now in the first place I would draw attention to the narrowness of Mr. Buchanan’s view. The only young man who seems to come within his ken is that one in a thousand or two who writes for his living. As a matter of fact, of course, the modern young man is learning to cure disease, to preach the Scriptures, to sell food and clothing; is building bridges, experimenting with chemicals, exploring and colonising and inventing; is behaving very much as his father did before him. In the mass he is about as incredulous of Arden as his father was, and doesn’t know who in the world Emma Bovary may be. But when he does follow after literature—a rare case—I fancy, judging from the occasions on which I have met him, that he shares with Mr. Buchanan the honour of admiring As You Like It, and possesses the further advantage (denied apparently to Mr. Buchanan) of admiring “Madame Bovary” too. I cannot see, for my part, that to love Shakespeare thoroughly you must loathe Flaubert. And yet, reading Mr. Buchanan’s essay with care, I am forced to conclude that he bases his invective on some such assumption as this. This, for instance, is what he says of Mr. Henry James:—“For him and his, great literature has really no existence. He is secretly indifferent about all the gods, dead and living. He takes us into his confidence, welcomes us into his study, and we find that the faces on the walls are those, not of a Pantheon, but of the comic newspaper and the circulating library. . . . These, then, are the glorious discoveries of the young man’s omniscience—George Eliot, Alphonse Daudet, Flaubert, Du Maurier, Mr. Punch, and the author of “Treasure Island.” Was there ever a more curious assumption? Because Mr. Henry James has chosen to write a book of essays about certain authors and books, he is “secretly indifferent” about other authors and books. Because he knows Daudet personally—and for this or other reasons feels himself able to tell the world something about Daudet—Dante and Milton have “really no existence” for him! Now as a young man I should like to ask these vehement elders a question—What do you think to effect by all this? You are for ever talking of the big men of old, of Shakespeare, Milton, Dickens, Thackeray. Do you want us to pretend to be Shakespeares and Thackerays when, as a matter of fact, we are nothing of the kind? Or to pretend to see and think things that Shakespeare and Thackeray saw and thought, when in truth we cannot? We will even grant that the biggest man nowadays may be the man who most nearly approaches those dead masters: still, would it be short of lying for us to dissimulate our probably inferior and certainly different perceptions? Again, you reprove us for what you are pleased to call the “pseudo-scientific” character of our attempts in fiction and the arts. Well, assuredly it is wrong to be pseudo-anything, pseudo-scientific no less than pseudo-classical. But will you seriously contend that we have no business to be influenced in our work by the additions which this last half-century has made to man’s knowledge, or the curiosity which this new knowledge has stimulated? Is it mere wanton folly for an artist to belong to his own age? To take an instance, is a work of art to be condemned out of hand if it show any acquaintance with recent discoveries in the matter of heredity? Lastly, would it not be better if we used our pens about each other less freely and tried to emulate the decency of other professions? ___

The Yorkshire Post (29 April, 1891 - p.3) Mr. Robert Buchanan is one of those persons who have a faculty for exciting opposition. His own pugnacity may have something to do with this, for he is never happy unless fixing a quarrel upon some section of society or some individual in it. Nor can we always persuade ourselves that he means to be taken seriously. There is an ever-present tendency to feel that he cannot be half as ferocious, half as uncompromising, as he would have us believe. He reminds one now and then of the iconoclastic demagogue in Hyde Park, who, after breathing out threatenings and slaughter for the space of an hour, was presently seen wheeling a perambulator with a meekness that could never have been assumed. But, whatever his subject, he is at least never dull. Like Mr. Runciman, he has a nice taste in invective, and can denounce an adversary with a diction copious and varied enough to be the envy of men who feel their own denunciations to be flat and insipid by comparison. In the volume entitled “The Coming Terror” (W. Heinemann) he has thrown together a variety of articles and communications conceived in a more or less truculent spirit. He is ready to defend his description of Ibsen as “a Zola with a wooden leg,” or dismiss Zola himself as “a dreary and dismal gentleman whose mind is solely exercised on questions of moral drainage and social sewerage,” or denounce “the modern young man,” or hit off Paul Bourget by telling us that “if we could imagine Zola and Ouida collaborating on a story to be afterwards revised by Mr. henry James, we should get a very good idea of a work of M. Paul Bourget.” Much of the book has so recently appeared in the newspapers that we have not had time to forget it, but the reader will find it at least amusing to renew his acquaintance with the whole collection. He may not agree with Mr. Robert Buchanan, but he will never be bored. ___

The Birmingham Daily Post (1 May, 1891 - p.3) Here are some of the epithets which Mr. Robert Buchanan applies to his contemporaries: Mr. Labouchere is “the Scapin of politics,” Mr. Robert Louis Stevenson “a hard-bound genius in posse,” Mr. William Archer “a saturnine severe young gentleman” in a “cheap literary suit,” Mr. John Morley “a belated Hume whose mind had been nurtured on the gospel of the Hall of Science,” Mr. Andrew Lang “a very typical Cockney,” Ibsen an “arid writer” who is “the dustman of a suburb,” while Zola is “the scavenger of a city.” ___

The Speaker (2 May, 1891 - pp.529-530) MR. BUCHANAN’S OPINIONS. THE COMING TERROR: and other Essays and Letters. By Robert Buchanan. London: William Heinemann. 1891. WE have already spoken of the temper displayed by Mr. Buchanan in this volume, and of the immoderate language which he is pleased to use towards men with whose work he disagrees. We dwelt on these features first for a very good reason. Resistance to new opinions is profitable, even if the opinions are sound: it compels the enthusiast to be definite, and to trim his creed of excrescences: it clears up the haze, and concentrates the battle on a plain issue. There is no harm in a reactionary who boldly stands in the path and says, “Go back to the eighteenth and even to the seventeenth century. Shakespeare and Milton possessed the final truth, and all the discoveries of science since their time are only leading you further and further astray.” But Mr. Buchanan is a very peculiar reactionary. As a castigator censorque minorum he might do, if only he displayed a worthy appreciation of the times he loves better to commend. But, as a matter of fact, the only feature of those times which he has been at pains to reproduce is their unchastened violence of speech. A man might as intelligently prove his devotion to the robust age of the Georges by setting up as a highwayman, or pay tribute to the spacious times of some earlier monarchs by erecting a private gallows. (1) “So far from having the Abominable hushed up and well regulated, I would have it flaunted publicly, in all its hideousness till the real truth is understood—that it is a creation of the filth of man’s heart , and that the class called ‘fallen’ is practically a class of martyrs.” Now we have nothing whatever to blame in these two statements of opinion. But with regard to the first we would simply test it by the touchstone of another sentence which occurs twice in “The Coming Terror.” Speaking with obvious reference to an episode in the history of the Pall Mall Gazette, Mr. Buchanan refers to “the publication of a scandal so infamous, and described so infamously, that the very air of Nature was polluted as by a cesspool, the stench of which penetrated like poison into every household of the land.” There is surely some want of lucidity here. In one breath Mr. Buchanan desires that the Abominable should be flaunted publicly in all its hideousness, and in another he speaks in terms of violent disgust of just such an attempt as he recommends—an attempt, too, that avowedly meant to show “that the class called ‘fallen’ is practically a class of martyrs.” plená pluviam vocat improba voce, ___

Truth (14 May, 1891 - pp.35-36) LETTERS ON BOOKS. MY DEAR MR. WYNDHAM,—There are two ways of procuring for yourself a factitious vogue in the literary world, first, log-rolling, i.e., mounting on your friends’ shoulders, on the condition of mounting them in turn upon your shoulders; and secondly, knocking them down to add a foot to your own stature by standing on their prostrate bodies. For literary men who, like Sneer, are “as envious as an old maid verging on the desperation of six-and-thirty,” log-rolling is out of the question; since the praising of their rivals would pain them more than the praise of their rivals would please them. They, therefore, must needs rise, if they are to rise at all, “on stepping-stones” of the dead bodies of others. When the aspirant is an admirable Crichton—poet, dramatist, philosopher, novelist, and critic—and has therefore rivals in every field, the carnage is proportionately terrific. You can imagine then that I rose from reading Mr. Robert Buchanan’s “The Coming Terror” (1) in spirits as depressed as Pip’s after a night with Mr. Wopsle, when that stage-struck parish clerk had revealed to him his resolution “to begin with reviving the Drama, and to end with crushing it; inasmuch as his decease would leave it utterly bereft and without a chance or hope.” Where shall we go for criticism when the little that is not immortal of Mr. Robert Buchanan dies? “One can follow with amusement the subacid sneers of Hazlitt—a cockney in its worst and earthliest sense—the florid flourishes of Macaulay, the sledge-hammer blows of Carlyle, the screaming invective of Mr. Ruskin; “while Matthew Arnold is “jejune and bitter,” and Mr. Andrew Lang is a “chirpy prophet” and feather-brained, “who has adopted the moral philosophy of Mr. Puff and the worldly wisdom of Mr. Dangle.” By the way, apropos of this onslaught on the critics, will you believe that Mr. Buchanan, in slating Gifford and Jeffrey among the rest, is under the impression that the Edinburgh Review was started in opposition to the pre-existing Quarterly? “The great Cockney organ of opinion is still the Quarterly Review. Many years ago the standard of revolt was raised in Edinburgh by the Whigs, and the Edinburgh Review was started.” Whereas, I need not say that, while the first number of the Edinburgh was launched in 1802, it was not until 1808 that John Murray started the Quarterly. But to return to the darkness that will cover the earth when Mr. Buchanan— Fair as a star, when only one has shot back to his own celestial sphere. Hazlitt, being dead—extinctus amabitur idem—is at least allowed to have some pretensions to critical powers; but there is no living critic except Mr. Buchanan, nor dramatist except Mr. Buchanan, nor novelist except Mr. Buchanan, nor philosopher except Mr. Buchanan and Herbert Spencer, nor poet except Mr. Buchanan and Tennyson. Zola is “a dullard au fond;” Henry James and Paul Bourget “are both omnisciently silly;” Robert Louis Stevenson “is a hard-bound genius in posse;” his “Treasure Island” is “a story of reminiscences of better stories, its one striking character being a bodily theft out of the pages of ‘Barnaby Rudge;’ and his ‘Child’s Garland of Verse’ as poor and made-up a matter—from any child’s point of view—as one can well conceive;” Messrs. Pinero’s and Grundy’s dramatic attempts are beneath contempt; Mr. Swinburne sings the “apotheosis of the coral and the lollipop;” Matthew Arnold brought forth two respectable poems and then ceased bearing; Goethe “is a tedious, a tiresome, and a dilettante writer,” to whom we go only “for intellectual concupiscence”—whatever that may mean. In a word, by a process of exhaustion we come to the inevitable conclusion that there is but one God—or Goddess, rather, woman—and that Robert Buchanan is her prophet. For you are again and again assured that “woman will never be the equal of man, because she is so infinitely his superior.” Even intellectually she is at least man’s equal; since “the names of Mary Somerville, of Georges Sand, and of Mrs. Browning, and of many others are sufficient to establish that women of genius are tall and strong enough to stand beside men of genius now and for ever.” That is to say, because half-a-dozen women are 6 ft. high, the average height of the sexes is equal. But, you see, woman, no more than the dead, come into competition with Mr. Robert Buchanan, and he is free, therefore, to use both for the belittling of his living rivals. Mr. Buchanan’s voice screams its shrillest in Billingsgating Mr. George Moore—not a favourite author with me as you know; yet I do not see the exquisite humour of calling that High Priest of Balzac a literary Jack the Ripper, whose vanity, ignorance, indecency, and courage are colossal. If Mr. Buchanan concentrated for years his dissipated faculties and energies on a novel, he could not produce one having a hundredth part of the power shown in Mr. Moore’s “Mummer’s Wife;” while a little volume of essays of his I have just been reading—“Impressions and Opinions” (2)—are infinitely better worth your reading than “The Coming Terror.” You will, I admit, be now and then disgusted with such hysterical twaddle as this:— To me there is more wisdom and more divine imagination in Balzac than in any other writer; he looked further into the future than human eyes could see (!); and that I am finishing these pages with tears in my eyes, that I have written so many upon five or six short stories, and could have written as many more, so rich in thought is his very slightest page, is a tribute to his genius, if such a rushlight as myself may pay tribute to such a miracle of glory as he. Or, again, as this about Balzac’s description of Rose Cormon’s leg:— A sinewy leg with a small calf, hard and pronounced as a sailor’s. “When I came upon the description of her leg, the book dropped from my hand in admiration of the master’s genius. The whole of Rose Cormon is in that wonderful leg.” Professor Owen’s bird’s bone, Lord Burleigh’s shake of the head, and M. Jourdain’s Turk’s “Bel-men,” which took half a page to translate, are nothing in power of hieroglyphic expression to the calf of the leg of Une Vieille Fille. Mr. Moore, you see, is suffering from a kind of D. T. attack of the Lues Boswelliana—so virulent, indeed, that he protests “he would willingly give up ‘Hamlet,’ ‘Macbeth,’ ‘Romeo and Juliet,’ &c, &c, for the yellow books”—yet, though his criticisms are shrill and strained, they are worth reading, and are, moreover, interesting reading. By the way, as I have given you Mr. Robert Buchanan on Mr. George Moore, I ought in justice to give you Mr. George Moore on Mr. Robert Buchanan. “Mr. Robert Buchanan is a minor poet and a tenth-rate novelist. . . . . In prose fiction he is either commonplace or ridiculous. . . . . His novels are clumsy and coarse imitations of Victor Hugo and Charles Reade. See how these Christians love one another! If, on the other hand, you desire to hear all, and more than all, that can be said for Mr. Buchanan as a novelist, you will find it in a volume which has other and juster claims upon your notice, Mr. John A. Steuart’s “Letters to Living Authors” (3) I cannot honestly say that these Letters are either original, brilliant, or profound; that there is anything in them which has not been said, and better said, before; but they are sufficiently light and bright to pass an idle hour, and the book has the great advantage of being illustrated by portraits of all but one of the authors criticised. I wish, though, that Mr. Steuart had given clearer cues for laughter; since his jokes are not always exactly overpowering. Are you expected, for instance, to smile at this brilliant pleasantry? “I think you could have written a good boy’s book. (I don’t mean a book for good boys).” . . . DESMOND B. O’BRIEN. (1) “The Coming Terror,” and other Essays and Letters. By Robert Buchanan. (London: William Heinemann.) ___

The Birmingham Daily Post (15 May, 1891 - p.5) Mr. Robert Buchanan’s latest work, “The Coming Terror,” has reached a second edition, to be published in a few days by Mr. William Heinemann. This will contain a special “Note” by the author, retorting in characteristic fashion upon his critics, and congratulating himself “on a fair measure of old-fashioned abuse.” “To have been saluted amicably by the Wooden Walls of Cockneydom,” cheerfully observes Mr. Buchanan, “would have been proof positive that my little vessel contained nothing but sailing orders for the lumbering Literary Fleet and complimentary messages from headquarters to the blundering gentlemen in command.” ___

The Speaker (16 May, 1891 pp.584-585) A SECOND edition of MR. ROBERT BUCHANAN’S “Coming Terror” appears with a “note” by the author, in which that gentleman, after mentioning the Times, Observer, and SPEAKER, adds, “Altogether I have to congratulate myself on a fair measure of old fashioned abuse.” But MR. BUCHANAN is not wholly in the self-complacent mood. He is angry at any allusion having been made to his temper, and assures the world—with quite unnecessary emphasis—that he is “a singularly calm person” who writes “quite coolly and good-humouredly.” We take note of his statement, which furnishes fresh evidence of the fact that the style is not the man. ___

The Liverpool Mercury (20 May, 1891 - p.6) LITERARY NOTICES. MR. BUCHANAN’S NEW BOOK.* Somebody ventured to indicate, without conveying the opinion in so many words, that Mr. Buchanan himself was the “coming terror”; but the inference, even if intended, was not wholly true, because Mr. Buchanan is in no sense “coming,” as he has long been a good deal of a terror in certain quarters. What he will be in the future remains to be seen, but in the past he has shown indomitable pluck in defending any position he has taken up, and rarely shows much mercy to an opponent. He really confesses himself fond of a tussle with the enemy, and the public, very often much in the position of idle spectators, rather like to watch the contest. The book before us is quite unlike either “A Poet’s Sketch Book” or “A Look Round Literature,” and has less literary interest than anything we should expect from a novelist, a poet, and a dramatist. All the same, “The Coming Terror” is vastly entertaining, and every page contains statements which might fairly give rise to much contradictory criticism. Dealing with socialism, Mr. Buchanan’s main contention is “that no amount of political or social tinkering will complete the process nature chooses to work out by her own slow methods of conscientious evolution, and that, by the present growth of quasi-providential restriction, by the emergence of mob morality and mob rule, those sublime methods are being indefinitely retarded, even occasionally reversed.” Mr. Buchanan deals with many other questions. “Are Men Born Free and Equal?” “Is Chivalry Still Possible?” “Is the Marriage Contract Eternal?” are only a few of the topics dealt with. He treats “The Modern Young Man as Critic,” but we rejoice to say that the application of the attack is limited. Mr. Buchanan enters a strong plea on behalf of the absolute liberty of the press, and, speaking of the Burns carnival every year, says—“Were I a Scotch poet, living or dead, I should prefer a very little sober appreciation to any amount of drunken idolatry; and I should not care to gauge the height of my success by the depth of degradation into which I had plunged my votaries.” In a word, let us say that “The Coming Terror” must arouse the interest of every one who takes up the book; and that it will give rise to much serious thought we cannot doubt, both by reason of the subjects treated and the masterly manner in which the author handles his arguments. *The Coming Terror, and other Essays and Letters. By Robert Buchanan. London: Heinemann. ___

The Arbroath Herald (28 May, 1891 - p.2) A GOOD story is told of Robert Buchanan’s new book, “The Coming Terror.” The title page of the first copies read, “The Coming Terror”—Robert Buchanan. The author saw the joke, the volumes were recalled, and a “By” was inserted. ___

Hull Daily Mail (28 May, 1891 - p.2) In the preface to a new edition of his latest book, Mr Robert Buchanan informs the world that he is “a singularly calm person,” who writes “quite coolly and good-humouredly.” This is news, indeed. Then, if Mr Buchanan ever got into a passion, what things he would say! ___

The Graphic (30 May, 1891) THE COMING TERROR UNDER this title Mr. Robert Buchanan has published a volume of essays and letters on topics of the day, in which he lays about him as with a flail, affording rare sport to the onlookers who are out of the reach of his arm. The first essay, though it takes the objectionable form of a dialogue between Mr. Buchanan and a dummy figure, is worth study for the timely warning it holds out as to the future the tyranny of the odd man is preparing for us. But Mr. Buchanan is strangely unequal; he is in such a hurry to score his points that he frequently overstates his case, and weakens his argument where a little discretion and reticence would have strengthened it. The same fault runs through all the other essays. No one will object to Mr. Buchanan dancing upon the prostrate body of the Young Man, though even here he is more than a little unjust; but the lust of battle is so strong in him that whenever he sees a head he cannot refrain from hitting it, even though it be a reverend or an able one. Mr. Buchanan battling with strong words for things which are noble and pure and of good report is altogether admirable, but he should beware of excess of zeal, and remember that he himself is not infallible, and has written works for the stage which do not conform exactly to the severest canons of Art for Art’s sake only. Still it is good to see a man wield his pen vigorously, even though there is occasionally more force than direction in his blows. Mr. Heinemann is the publisher of the volume. ___

The Academy (6 June, 1891 - No. 996, p.581-582) The Coming Terror, and other Essays and Letters. By Robert Buchanan. (Heinemann.) TO reprint newspaper letters in a volume forms a bad precedent. For already too much journalism gets itself enclosed in cloth bindings; and, if the contents of even the correspondence columns are, henceforth, to flood the book-market, what is to become of the bewildered reader? All letters are not as clever as Mr. Buchanan’s; yet, even in his case, considering the importance of the subjects he discusses, a more deliberate and finished statement would have been acceptable In this volume, in addition to the letters, are two or three essays from magazines, a quantity of “Flotsam and Jetsam,” and no less than eight separate sets of “Final Words.” Nevertheless, the collection is not a mere miscellany. It has a common object, namely, to exhibit and denounce the various phases of “the coming terror.” "Leave the drains alone; let the world wag, even if typhoid fever should flourish. Moral number two, very acceptable to the average insular intelligence: conceal from all clean people, especially young people, the fact that there is any sewerage at all” (pp. 104-5). As to Zola himself and his “pornography,” Mr. Buchanan says: “I have always been Puritan enough to think pornography a nuisance. It is one thing, however, to dislike the obtrusion of things unsavoury and abominable, and quite another to regard any allusion to them as positively criminal. A description even of pigsties, moreover, may sometimes be made tolerable by the cunning of a great artist; and this same M. Zola, though a dullard au fond, for the simple reason that he regards pigsties as the only foreground for his lurid moral landscapes, appears to be so much better than myself, in so much that he loves truth more and fears consequences less, that I have again and again taken off my hat to him in open day. His zeal may be mistaken, but it is self-evident; his information may be horrible, but it is certainly given in good faith; and an honest man being the rarest of phenomena in all literature, this man has my sympathy, though my instinct is to get as far away from him as possible” (p. 105). The protest and appeal did not serve the ostensible end. Mr. Henry Matthews was not moved by it to grant Mr. Vizetelly relief; and, it must be confessed that, with all its excellencies, it was not well designed to secure any such result. It recalls to mind the German advocate who, being appointed to defend a Socialist in the days when Socialists were considered criminals, took the opportunity of expounding his own extreme doctrines, in language which he would not have dared to use on any other occasion. The trial ended, he sought the friends of the prisoner, and announced, “A glorious triumph.” “Is he acquitted then?” asked the friends. “Oh, no!” was the reply; “he is to be executed; but I have declared our great principles in open day.” “was feather-headed but earnest; impulsive and uninstructed, but sympathetic and occasionally studious. . . . A great thought, even a fine phrase, stirred him like a trumpet. . . . But now, with the passing of one brief generation, the world has changed; the youth who was a poet and a dreamer has departed, and the modern young man has arisen to take his place” (p. 146). A sad falling-off indeed from his earnest if feather-headed predecessor, for the modern young man is “a saturnine young man, a young man who has never dreamed a dream or been a child, a young man whose days have been shadowed by the upas tree of modern pessimism, and who is born to the heritage of flash cynicism and cheap science, of literature which is less literature than cynicism run to seed” (p. 146). Allowance, however, must be made for the different points of view of the seer. It was with the half-inward gaze of youth that he saw the young man of his own youth; and he is regarding the young man of to-day with the wider, more critical, and more experienced observation which comes when youth is past. Probably that young man of the past was no more than the somewhat idealised portrait of himself as he was or aimed to be. Young men do not study other young men with any considerable amount of critical discernment. The world as they know it is the world as they see it in their conscious selves. “it is fast becoming forgotten; that the old faith in the purity of womanhood which once made men heroic, is being fast exchanged for an utter disbelief in all feminine ideals whatsoever, and that women in their turn, in their certainty of the contempt of men, are spiritually deteriorating” (p. 186). The whole outlook is appalling: “Nothing certainly can be more terrible than the existing condition of things, both social and political” (p.97). It is well Mr. Buchanan tells us he is an optimist, for he would be sadly misunderstood. ___

The Boston Daily Globe (27 July, 1891 - p.6) NEW LITERATURE. Robert Buchanan’s Essays ... A reprint of Robert Buchanan’s “The Coming Terror and Other Essays and Letters,” will powerfully influence thought in this country, as it is doing in England, where a third edition is called for. New York: United States Book Company. Boston: De Wolfe, Fiske & Co. ___

The Theatre (1 August, 1891) “The Coming Terror,” by Robert Buchanan. (Heinemann). From the first moment Mr. Buchanan began to write, he has been endeavouring, he assures us, to vindicate the freedom of human personality, the equality of the sexes, and the right of revolt against arbitrary social laws conflicting with the happiness of human nature. It would appear, then, that his aims and Ibsen’s are identical. Yet, strange to say, Ibsen is singled out, in this second essay upon “The Gentle Art of Making Enemies,” for the weightiest missiles of contumely and wrath! This fact is the key to Mr. Buchanan’s seemingly irreconcilable contradictions. He must and will stand alone. His foot is on his native heath and he’ll hack and slash at all, till the crack of doom. His Individualism shall be actual. There shall be none like unto him, neither in the heavens above, nor on the earth beneath, nor across the waters of Acheron that are under the earth. For this the man is to be admired. The splendid audacity of the challenge, the glove flung down by one to millions, reconciles us to a hundred worthless foibles, and a thousand unjust and hasty verdicts. The spirit Macaulay breathed into Horatius stirs within us still. “For how can man die better than facing fearful odds For the ashes of his fathers, and the temples of his gods.” The sentiment which leads us to canonise Robert Bruce, and to accept Rider Haggard as a novelist, now urges us to read every page of “The Coming Terror,” and thank its author for having written it. Within its covers we find a literary Umslopogaas, and the play he makes with that deadly axe of his is worthy of Mr. Haggard in his most Homeric vein. No odds are too great. The Home Secretary, “the new Pilate Punchinello;” ex-Justice Stephen, “the Caiaphas of the Bench;” Mr. Labouchere, “the Paul Pry of journalism, and the Scapin of politics;” Professor Huxley, “a moral troglodyte;” Emile Zola, “a merry and dismal gentleman” devoted to “questions of moral drainage and social sewerage;” Lord Wolseley, “a droning Military Person;” Paul Bourget “ridiculus mus of a social mud heap in parturition;” Henry James, “a fatuous young man;” Ouida, “that classic of the Langham;” Guy de Maupassant, “whose lovers find out each other, like animals, by the sense of smell;” Mr. William Archer, '”a dull young man of saturnine proclivities; “Mr. George Moore, “a cockney Bohemian of the Latin Quarter;” Mrs. Lynn Linton, his “matron militant;” Mr. John Morley, “a belated Hume;” Louis Stevenson, “a hard bound genius in posse;” Mr. Andrew Lang, “the prophet of modern Nepotism;” Mr. Rider Haggard, “a teller of tales to the marines, a disseminator of the philosophy of the preposterous;” Huxley again, “the Pharisee who passes by,” “the quasi-scientific Boanerges;” “the impeccable albino, Mr. Howells;” “the nerve-shocking, negroesque M. Zola;” are a few of the adversaries this braw Scot, with Gargantuan appetite for slaughter, sets himself to demolish. Up swings razor-edged “In kosi kaas” and down it comes with sledge-hammer force, maiming, disfiguring, crippling, and strewing the ground with corpses. The Grand Old Zulu, to continue the metaphor, never falters. Not for an instant does he pause for breath. He is fleet of foot, supple of limb, and never a blow does he strike in vain. The lust of war is in his flaming eye and his distended nostrils. And a good deal of sympathy must go out to this dauntless warrior who keeps the bridge against an army. Mr. Buchanan’s pungent and pregnant sentences always repay perusal, but of “The Coming Terror” more than that may with justice be said. It is indeed something of a rara avis, a store of original thought and lively speculation, without a dull page to endanger its worth. ___

Northern Daily Mail (18 August, 1891 - p.2) THE COMING TERROR. MR ROBERT BUCHANAN is best known to the British Public as a poet, novelist, and dramatic author, but on occasion he can throw aside the poetic muse, quit the weaving of intricate plots, and the high falutin’ language of melo-drama, and figure with more or less—according to the judgment of the reader—success as a serious essayist. Ever and anon the clever author of “God and the Man,” “breaks out in another place,” so to speak. He has just published through the medium of the house of Heinemann “The Coming Terror, and other Essays and Letters.” Mr Buchanan is fearful of the future. He believes there is social danger ahead, and the Coming Terror he writes of is that of “the majority trampling down the rights of the minority.” This unhappy state of things he thinks is being hurried on by over-legislation and “the vulgar tyranny of the New Journalism,” but, although Mr Buchanan dogmatises at length, he adduces very little in the way of argument or logical reasoning to support his theory that the Coming Terror which has moved him to write this essay is really coming. There is a good deal of egotism—maybe unconscious egotism—in Mr Buchanan’s book. He has been at pains to tell his readers in rather wearisome detail what Robert Buchanan has done, and written, and what Robert Buchanan thinks. This probably is very interesting to Robert Buchanan, but his personality is not sufficiently potent to influence the masses of the people either one way or the other. He tells us in the present volume that he is an advocate of the “higher socialism,” and, further, that from the earliest day of his literary career he has been “endeavouring to vindicate the freedom of human personality, the equality of the sexes, and the right of revolt against arbitrary social laws conflicting with the happiness of human nature.” This “higher socialism” appears to be a figment of the imagination of idealists such as Mr Buchanan, and it is not a little singular that those gentlemen who speak and write most about it have never condescended to define it, so that those of us who are less advanced in our ideas may learn something of its nature. |

|

|

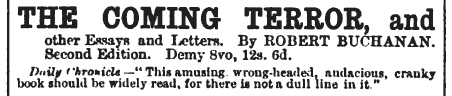

[Advert from The Academy (5 September, 1891 - No. 1009, p.188).]

Back to Reviews, Bibliography, Essays or The Coming Terror _____

Is Barabbas a necessity? A discourse on publishers and publishing. (1896)

The Newcastle Courant (22 February, 1896 - p.5) Mr Robert Buchanan has added to his fame by publishing a pamphlet to announce that he is to be in future his own publisher, and to tell the world why. “The barnacle on the bottom of the good ship literature” is the name he calls the publisher; but surely this must be the dramatic way of putting it. If certain publishers fail to agree with Mr Buchanan as to the exact merit of his literary work, surely this is no sufficient reason for denying a right of existence to publishers as a whole. Mr Buchanan has added to his fame in various unattractive ways lately, and this new move does not seem to suggest any improvement. ___

Glasgow Herald (3 March, 1896) “Is Barabbas a Necessity?” asks Mr Robert Buchanan, and he answers the question with a decided affirmative, in joining the ranks himself. It may, of course, be said that Byron’s opprobrious characterisation of the publishing trade applied only to publishers who acted for other people, not to men who published for themselves. Mr Buchanan, however, gives away his whole case by one simple act. He has set out on the adventurous path of publisher of his own books; but he also announces one other work which is to appear under his imprint, and in doing so he surrenders the very principle for which he contends with characteristic vehemence. He pleads, of course, that his offence in this direction is a very small one. The book is a mere “unpretending piece of farcical tomfoolery,” and he explains, with unconscious humour, that it “comes from a source so near to me that it may be considered more or less mei generis.” But the inherent unimportance of “The Adventures of Miss Brown” does not alter the fact that Mr Buchanan, at the very moment of flouting Barabbas, enrolls himself under the banner of that much-abused personage. While he denounces all existing publishers as “the barnacles on the ship’s bottom criticising the cargo in the hold,” he sets up in business himself as the barnacle on the cock-boat of “Charles Marlowe!” But nobody ever looked to Mr Buchanan for rigid and prosaic consistency. One is thankful to find him always amusing when, in his capacity of righter of wrongs, he goes forth to tilt at abuses and make mincemeat of his enemies. He has never been more amusing than in his latest diatribe against the “Highwaymen of literature,” “Messrs Barabbas, Macheath, Wild & Co.,” who interpose with “Stand and deliver” between the poor but honest author and his public, and who wax fat in the exact ratio in which the unfortunate producer of books wanes and becomes mentally and physically lean. With such remarkable qualifications for the part of funny man, it is sad to behold Mr Buchanan wasting them on the “eternal problems of Life and Death,” which could be quite well left in other hands, while comic journalism, at present so barren, offers him a field of infinite possibilities that he might make all his own. Meanwhile he has his hands sufficiently full. The eminent poet, novelist, essayist, biographer, and dramatist has added to his other avocations that of publisher, and a curious world will await with eagerness the result of his experiment. One must admire the lightness of heart with which he enters upon his new sphere of usefulness. But it is not surprising that he should do so. The ordinary existent type of publisher is a person who “grows fat and prosperous on the author’s foolishness, and whose heirs are rich men when the descendants of the author are being carried to the workhouse.” And yet his duties are simple and easy, and he comes to them equipped in the lightest possible manner. His main duty is to “stick his name” on the title page, and he frequently has difficulty in “accurately distinguishing between a manuscript and a millstone,” or in “knowing a book from a razor.” Why, then, should not a Great Poet (witness Marie Corelli) step into this royal road to fortune, and, in the intervals of solving the problems of life and death, acquire wealth beyond the dreams of avarice? ___

The Gloucester Citizen (3 March, 1896 - p.6) The publishers and the Authors’ Society will, no doubt, watch with amused curiosity the spectacle of an experiment by the enterprising and self-assertive Mr. Robert Buchanan as author-publisher. Mr. Buchanan henceforth will be his own publisher, and will have no more dealings with the mere commercial publisher, whom he describes as “the barnacle on the bottom of the good ship Literature, yet presuming to criticise the quality of the cargo in the hold.” Here be tropes, metaphors, and similes. Mr. Buchanan should reserve himself for a duller season, when the public has nothing of real interest to think about. ___

The Sheffield and Rotherham Independent (6 March, 1896 - p.5) In Mr. Robert Buchanan’s pamphlet, “Is Barabbas a Necessity?”—which, by the way, is published by the author—we come upon a little bit of personal gossip (says the “Literary World”) which will greatly amuse the author of the book called “Barabbas.” [The “necessity” of Mr. Buchanan’s title does not refer, we should interpolate, to the lady’s book, but to the typical publisher.] “Now, I like Miss Corelli. Whatever the authorised critics may say of her, she has won her public—a very large one—by sheer energy of pluck and talent. I have taken tea with her, and I have it in her own pretty handwriting that I am a Great Poet, that she sits (metaphorically) at my feet, and that she has drunk rapture and inspiration from my masterpieces of song. I was a little surprised, therefore, when she went out of her way, about a year ago, to call me ‘a Scottish Playwright,” and to say that ‘there would be something inexpressibly funny in a Robert Buchanan pronouncing doom on the Christ, if it were not so revolting.’ This, alas! after all the tea, all the missives on pink-tinted paper, and all the adoration! But I fancy that the angry little lady conceived, for some reason or other, that I was one of her adverse critics, and that I had inspired my friends to treat her writings cavalierly. She actually believed, I fear, that I, the very Ishmael of Authors, who never had a log rolled for me in my life, had been in league against her with the Nonconformist Conscience and the ‘Daily Chronicle!’ Hence the sudden and startling ‘’Tilda, I hate you!’ from Fanny to her dearest friend.” ___

New York Tribune (22 March, 1896 - p.26) Mr. Robert Buchanan has girded on his armor, that shining armor which rattles like a tin shop whenever he enters the arena, and has taken unto himself a citadel of publishing. From this he is issuing books and pamphlets. One of the latter is a kind of manifesto, called “Is Barabbas a Necessity?” the title and the pamphlet making the most of Byron’s well-known fling at the publishing fraternity. The publisher, in Mr. Buchanan’s view of the matter, is “a barnacle on the bottom of the good ship Literature, yet presuming to criticise the quality of the cargo in the hold.” It would be amusing to know what kind of a barnacle Mr. Buchanan considers himself to be. It is hardly credible that he will print the productions of any one who happens to demand that he should do so, waiving all rights of criticism, to say nothing of rejection. Considering the way in which Mr. Buchanan discusses most subjects that come under his notice, it is likely that he will have trouble in his new venture. The very authors who may join with him now in his query as to Barabbas—are they unlikely to ask the same question in regard to Mr. Buchanan, after the latter has been using some of a “publisher’s discretion?” Back to Reviews, Bibliography, Essays or Is Barabbas a Necessity? _____

|

|

|

|

|

|

|