ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

THE ‘AUDUBON CONTROVERSY’

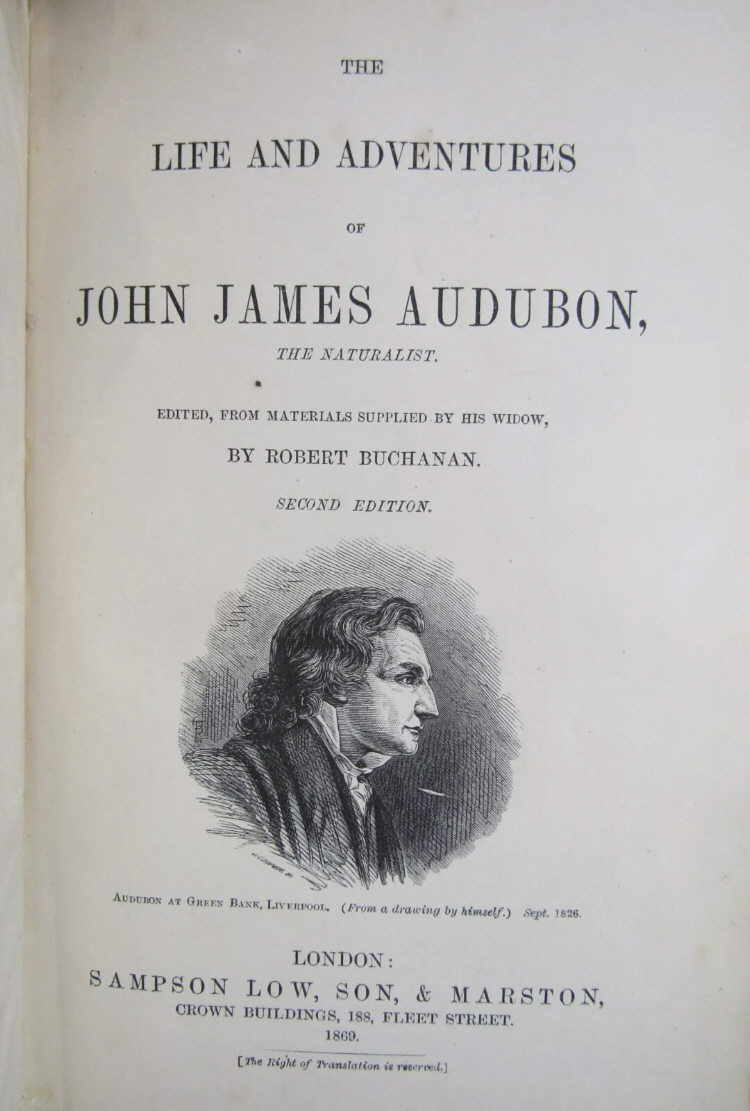

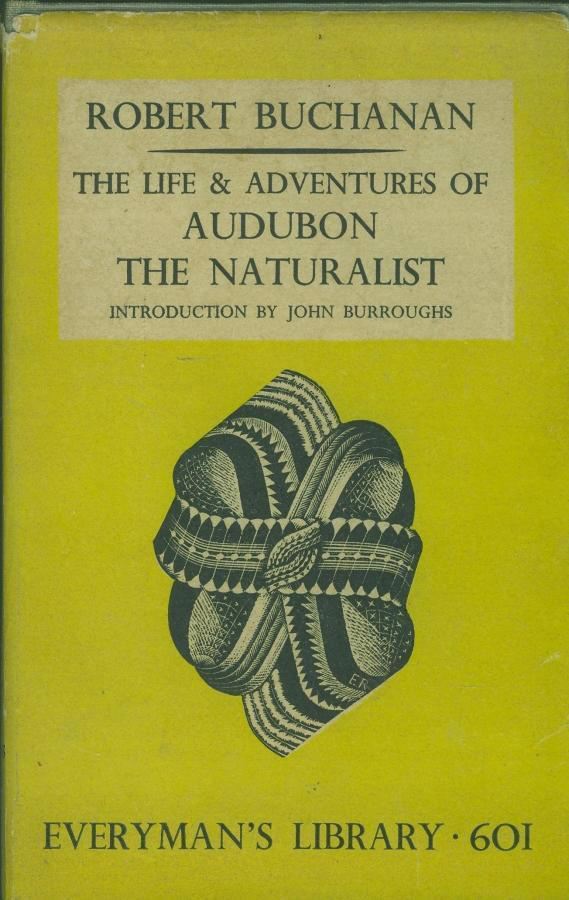

Robert Buchanan was commissioned by the publishers, Sampson Low, Son & Marston, to write a biography of John James Audubon, or, rather, to edit a manuscript and other materials supplied by Audubon’s widow. The resulting book, The Life and Adventures of John James Audubon, the Naturalist was published in 1868. It did not meet with the approval of Mrs. Audubon and, after three editions (and one in New York by E. P. Dutton & Co.), she prepared her own revised version of the work, with the help of James Grant Wilson. This was published in 1869 by G. P. Putnam as The Life of John James Audubon, the Naturalist. Then, in 1912, Buchanan’s original version was added to the ‘Everyman’s Library’ published by J. M. Dent & Sons in London and E. P. Dutton & Co. in New York. This resulted, rather ironically, in Buchanan’s The Life and Adventures of J. J. Audubon remaining in print far longer than most of his other works. To shed a little more light on the ‘Audubon controversy’, below are Buchanan’s Preface from his original edition, James Grant Wilson’s Introduction to the revised edition, and extracts from the Preface to Audubon And His Journals by Maria R. Audubon and the opening chapter of Audubon The Naturalist by Francis Hobart Herrick. |

|

|

|

|

|

The Life and Adventures of John James Audubon, the Naturalist (original edition) (available at the Internet Archive).

EDITOR’S PREFACE. IN the autumn of 1867, the present publishers placed in my hands a large manuscript called the “Life of Audubon,” prepared by a friend of Mrs. Audubon’s, in New York, chiefly consisting of extracts from the diary of the great American naturalist. It needed careful revision, and was, moreover, inordinately long. While I cannot fail expressing my admiration for the affectionate spirit and intelligent sympathy with which the friendly editor discharged his task, I am bound to say that his literary experience was limited. My business, therefore, has been sub-editorial rather than editorial. I have had to cut down what was prolix and unnecessary, and to connect the whole in some sort of a running narrative,—and the result is a volume equal in bulk to about one-fifth of the original manuscript. I believe I have omitted nothing of real interest, but I am of course not responsible in any way for the fidelity of what is given. The episodes, wherever they occur, I have given pretty much in full, as being not only much better composed than the diary, but fuller of those associations on which Audubon rests his fame. R. B. |

|

|

The Life of John James Audubon, the Naturalist (revised edition) (available at the Internet Archive).

INTRODUCTION. IN the summer of 1867, the widow of John James Audubon, completed with the aid of a friend, a memoir of the great naturalist, and soon after received overtures from a London publishing house for her work. Accepting their proposition for its publication in England, Mrs. Audubon forwarded the MSS., consisting in good part of extracts from her husband’s journals and episodes, as he termed his delightful reminiscences of adventure in various parts of the New World. The London publishers placed these MSS. in the hands of Mr. Robert Buchanan, who prepared from them a single volume containing about one fifth of the original manuscript. “That cheerful one, who knoweth all Her delightful volume will better speak for itself. Nor do I deem it requisite to dwell at length on the works of Audubon, pronounced by Baron Cuvier to be “the most splendid monuments which art has erected in honor of ornithology.” J. G. W. |

|

|

From the Preface to Audubon and his Journals by Maria R. Audubon (available at the Internet Archive). (pp. ix-x) “The Life of Audubon, the Naturalist, edited by Mr. Robert Buchanan from material supplied by his widow,” covers, or is supposed to cover, the same ground I have gone over. That the same journals were used is obvious; and besides these, others, destroyed by fire in Shelbyville, Ky., were at my grandmother’s command, and more than all, her own recollections and voluminous diaries. Her manuscript, which I never saw, was sent to the English publishers, and was not returned to the author by them or by Mr. Buchanan. How much of it was valuable, it is impossible to say; but the fact remains that Mr. Buchanan’s book is so mixed up, so interspersed with anecdotes and episodes, and so interlarded with derogatory remarks of his own, as to be practically useless to the world, and very unpleasant to the Audubon family. Moreover, with few exceptions everything about birds has been left out. Many errors in dates and names are apparent, especially the date of the Missouri River journey, which is ten years later than he states. However, if Mr. Buchanan had done his work better, there would have been no need for mine; so I forgive him, even though he dwells at unnecessary length on Audubon’s vanity and selfishness, of which I find no traces. M. R. A. |

|

|

From Chapter 1 of Audubon the Naturalist by Francis Hobart Herrick (available at the Internet Archive). (pp. 18-23) In 1868 there appeared in England a work of combined and confused authorship, commonly referred to as “Buchanan’s Life of Audubon,” the “sub-editor,” as he called himself, having since become better known as an original, skilled and prolific writer of verse, drama, fiction and literary criticism. At that time Robert Buchanan was twenty-six years old, and had published five volumes of poems in rapid succession, some of which had been received with favor by the public. A second and third edition of this Life followed in 1869. Finally the work was resurrected and again sent to press, unrevised, in 1912, when it appeared in “Everyman’s Library,” at a shilling a copy, with an introduction which had served as a review of the work in 1869. 11 Rev. Dr. Adams was rector of this parish for twenty-five years, from 1863 to his death in February, 1888; he was the author of three volumes on religious subjects and various smaller tracts; from 1855 to 1863 he had charge of a church in Baltimore, Maryland, and while there published an anonymous pamphlet entitled “Slavery by a Marylander; Its Institution and Origin; Its Status Under the Law and Under the Gospel” (8 pp. 8vo. Baltimore, 1860). Messrs. Sampson Low, Son, & Marston, who without any authority turned it over to one of their hard-pressed, pot-boihng retainers, Robert Buchanan, poet and young man of genius. Buchanan boiled down the original manuscript, as he said, to one-fifth of its original compass, cutting out what he regarded as prolix or unnecessary and connecting “the whole with some sort of a running narrative.” 12 Mrs. Audubon was unable to recover her property from either publishers or editor or to obtain any satisfaction for its unwarranted use. Whatever defects the Adams memoir may have possessed, this is much to be regretted, since, as her granddaughter has said, Mrs. Audubon had at her command many valuable documents, the originals of which have since been destroyed. 12 Buchanan said that the manuscript submitted to him was inordinately long and needed careful revision; he added that “while he could not fail to express his admiration for the affectionate spirit and intelligent sympathy with which the friendly editor discharged his task, he was bound to say that his literary experience was limited.” After copying a passage from one of Audubon’s journals, this editor had the unfortunate habit of drawing his pen through the original; in this way hundreds of pages of Audubon’s admirable “copper-plate” were irretrievably defaced. Audubon’s lifelong pursuits, any knowledge of ornithology, or any interest in natural science. Though expressing unbounded admiration for the naturalist, his foibles and faults seem to have hidden from this biographer the true value of his distinguished services. In respect to a knowledge of natural history it should be added that Buchanan laid no claims, and of Audubon’s accomplishments in this field comparatively little was said, the book, like the Adams’ manuscript from which it was drawn, being mainly composed of extracts from the naturalist’s private journals and “Episodes,” as he called his descriptive papers. It was here that Audubon made the strongest appeal to this literary editor, who concluded his preface with the following words of praise: “Some of his reminiscences of adventure . . . seem to me to be quite as good, in vividness of presentment and careful colouring, as anything I have ever read.” Audubon was a man of genius, with the courage of a lion and the simplicity of a child. One scarcely knows which to admire most—the mighty determination which enabled him to carry out his great work in the face of difficulties so huge, or the gentle and guileless sweetness with which he throughout shared his thoughts and aspirations with his wife and children. He was more like a child at the mother’s knee, than a husband at the hearth—so free was the prattle, so thorough the confidence. Mrs. Audubon appears to have been a wife in every respect worthy of such a man; willing to sacrifice her personal comfort at any moment for the furtherance of his great schemes; ever ready with kiss and counsel when such were most needed; never failing for a moment in her faith that Audubon was destined to be one of the great workers of the earth. 13 No one will deny, however, that Buchanan was right in saying that in order to get a man like Audubon understood, all domestic partiality, the bane of much biography, must be put aside; but it is equally important to make such allowances as the manifold circumstances of time and place demand, and to be a reasoner rather than a fancier. This work abounds in errors, but it is not clear to what extent they were due to carelessness on Buchanan’s part. 13 Robert Buchanan, The Life of Audubon (Bibl. No. 72), p. vi. Perhaps the best key to the sad history of this able writer was given by himself when he said: “It is my vice that I must love a thing wholly, or dislike it wholly.” His wife, we are told, was much like himself, and “like a couple of babies they muddled through life, tasting of some of its joys, but oftener of its sorrows.” Undoubtedly Robert Buchanan was a genuine lover of truth and beauty; he has written numerous sketches of birds and outdoor scenes, but with no suggestion of nature as serving any other purpose than that of supplying a poet with bright and pleasing images. ___

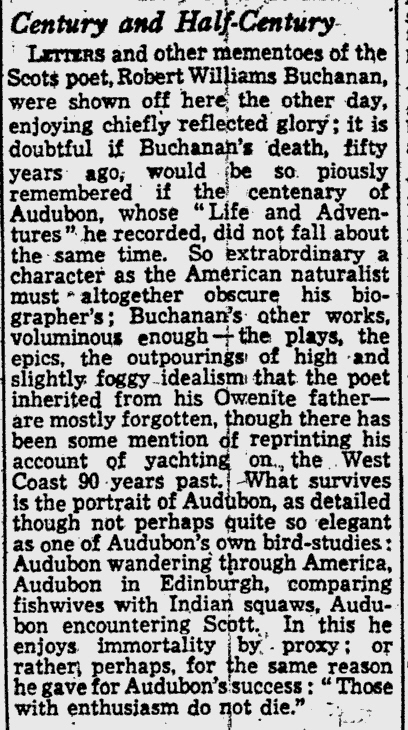

From ‘London Correspondence’ in The Glasgow Herald (13 February, 1951). |

|

|||

|

|||

|

Back to Book Reviews - Miscellaneous (1) or Bibliography

|

|

|

|

|

|

|